Systematic Approaches to Art-Making

That randomness is also (somewhat ironically) very explicit and rules-based. The algorithmic artist needs to craft a specific probability distribution in order to get the right kinds of random numbers.

Algorithmic artwork forces the artist to be very systematic in their work, because computers don’t take fuzzy or ambiguous instructions. The algorithm must be clear, precise, and thorough from beginning to end. You might suppose this is the opposite of how artists have historically worked. We tend to imagine painters working with passion and inspiration, following their intuition, and wordlessly summoning a vision. While this is undoubtedly true for some artists, history is also replete with artists who worked methodically, designing systems of rules to govern the execution of their art.

In fact, you can view an artist’s “style” as exactly this: a set of rules that the artist holds constant across multiple works. This gives their work a sense of unity. It may also help the artist to stick with what they think is most effective or interesting, and fully explore that potential space. If the artist is good, they are choosing these rules thoughtfully and with great care.

Algorithmic art simply takes this further. In its pure form, there is nothing but rules and randomness. Every single aspect and detail of the work must either be explicitly handled with a rule, or it must be explicitly turned over to randomness [1]. This means that the artist cannot, in the way we tend to expect, leave decisions to intuition or the subconscious. They must learn how to sort out their feelings and aesthetic preferences in a very concrete way.

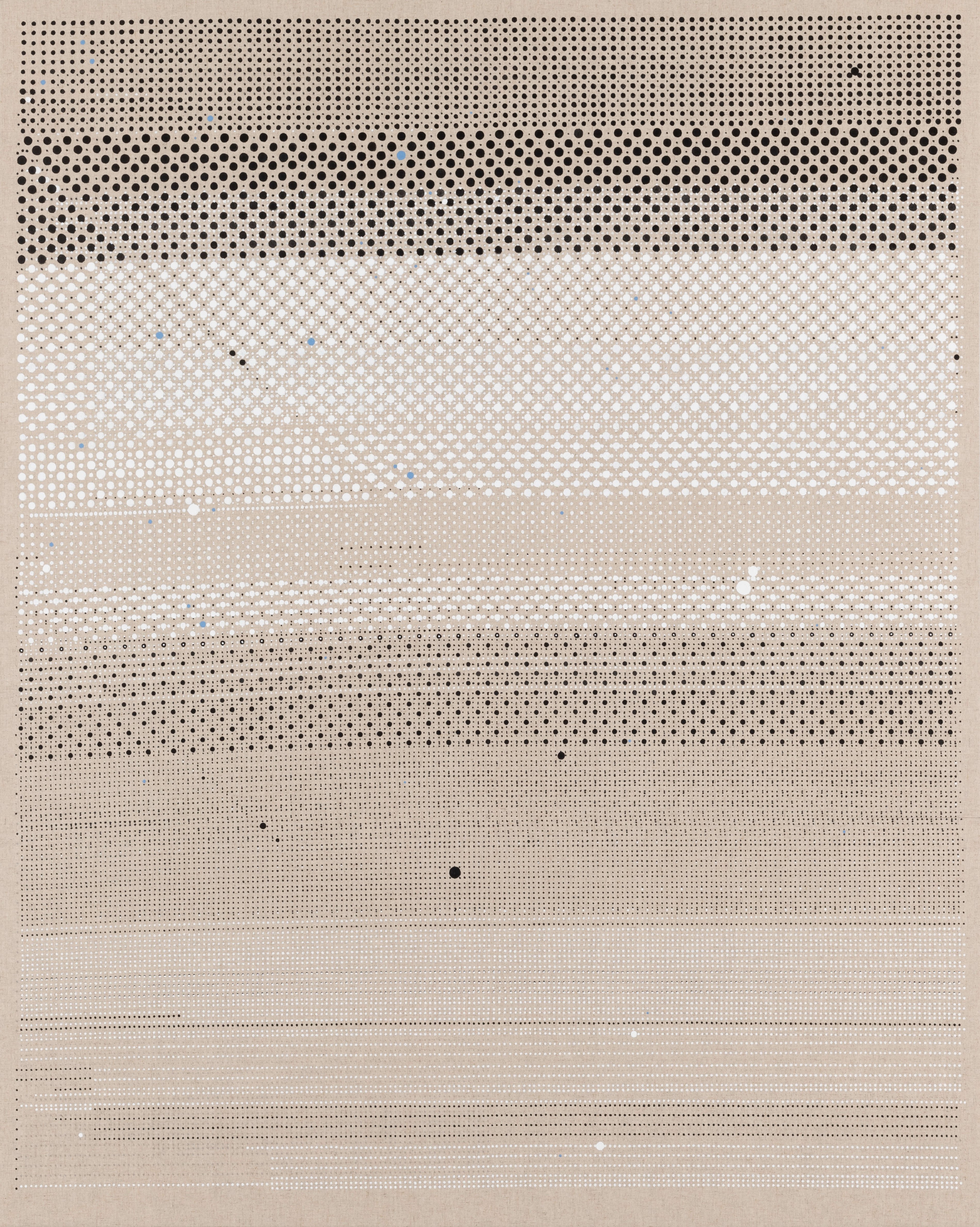

Jacquard Legacy, 2023

Detail

To give an example, suppose a generative artist is creating an algorithm that generates images full of dots. Some dots will be red, and the others will be blue. How many should be red or blue? Is it best if they are equal in number? Or is an asymmetric ratio more interesting? And if it is asymmetric, is a 1:3 ratio or a 1:10 ratio more dynamic? Perhaps the ratio can be 1:4 on average, but with randomness added to occasionally swing it all the way to 1:1 or 1:10. Building on that, perhaps if the ratio is above 1:2, should the spatial distribution of the reds be shifted in order to keep the composition balanced? And so on, for hundreds of further decisions. In this way, the algorithmic artist is forced to be entirely systematic in their work.

However, this is not to say that the generative artist must forego the use of their intuition entirely. Even though this way of working doesn’t utilize the artist’s intuitive decision-making in the way we expect (based on norms from more traditional media), that intuition is heavily involved in the way the different possibilities are explored, and in how core decisions are given over to randomness in order to create the potential for surprising, emergent results.

Modern hardware and software affords us the ability to construct systems that are more precise, complicated, and powerful than what those artists could explore by hand.

As the artist, you must spot good opportunities for expanding the generative system. Early versions of an algorithm are often filled with simple, strict decisions. These can typically be softened and loosened. Carefully employed randomness can transform static behavior into a fresh and surprising space of potential outcomes. This is desirable, because the generative artist is not looking for a singular vision, but rather a whole cloud of possible creations. Imagination and intuition are necessary to identify the most fruitful ways this can happen.

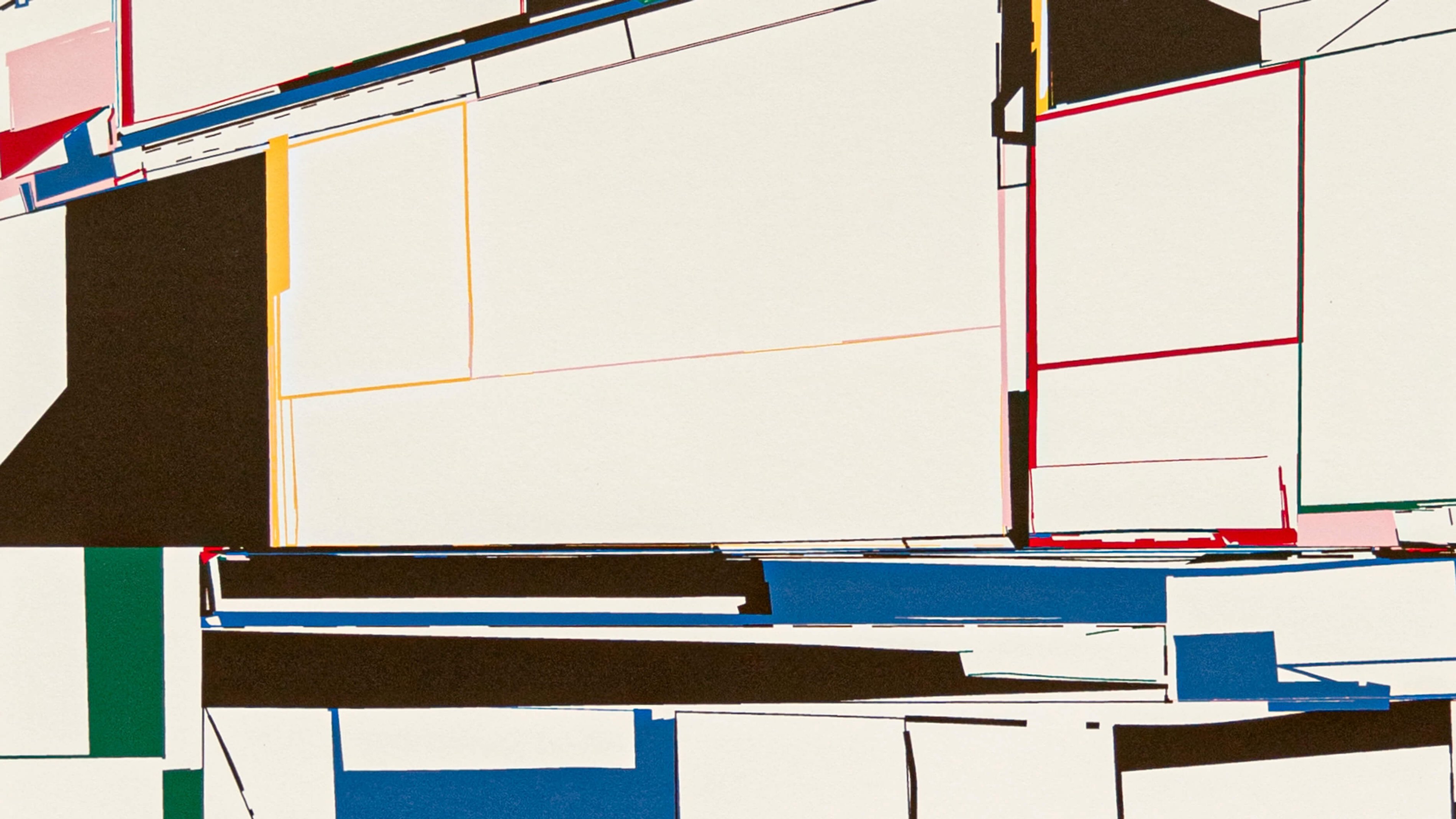

Connected, for the Moment 3, 2023

Some of the systematic decisions embedded in this algorithmic work are: picking acceptable ratios for splitting a shape in two; defining the set of available line thicknesses; creating a model for how curvature can be added to straight lines; managing the amount of curvature at large scales versus small scales; determining how and when negative space is preserved; balancing the ratio of large shapes to small shapes.

As I alluded to, this systematic approach to art-making is not limited to algorithmic art. Although no programming was involved, artists like Agnes Martin, Richard Diebenkorn, Piet Mondrian, and Sol LeWitt all adopted, to one degree or another, a systematic mindset within their work, and spent time exploring semi-generative spaces. In many ways, algorithmic artists are an extension of this lineage. Modern hardware and software affords us the ability to construct systems that are more precise, complicated, and powerful than what those artists could explore by hand. This has opened the door for algorithmic artists to explore new territory. While systematic artwork is not necessarily better or worse than any other mode of art-making, it is undeniably fascinating to see the results of extending that methodology to an extreme, all enabled by algorithms.

This essay is an excerpt from Hobbs' 2024 monograph, Order/Disorder.